If the UK’s self-employed do not start saving and investing for their retirement they will be working out their twilight days working, rather than relaxing. This is the stark reality revealed in a new report.

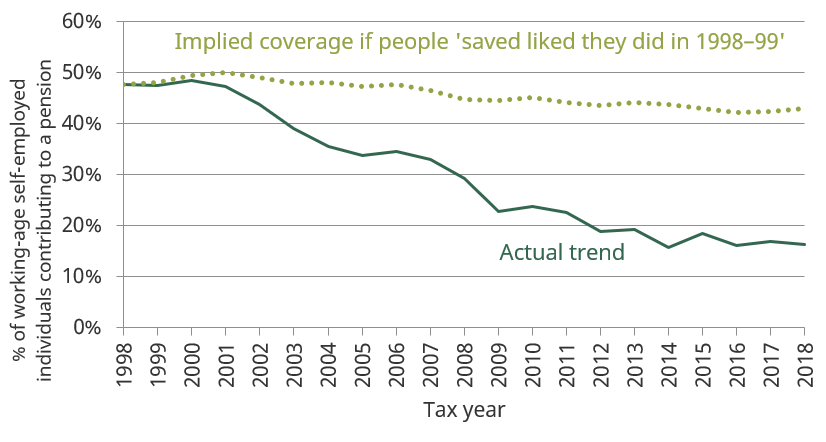

The proportion of working-age self-employed saving in a private pension has declined dramatically over the last two decades, from 48% in 1998 to just 16% by 2018. This suggests there are currently over 3.5 million working-age self-employed who are not saving in a private pension, The Institute for Fiscal Studies has revealed.

In sharp contrast, pension saving among employees has increased since the introduction of automatic enrolment – in 2018 nearly 80% of working-age employees were contributing to a pension. However, even before the introduction of automatic enrolment, the rate of decline in pension participation was faster among the self-employed than private-sector employees.

Participation has fallen more dramatically among those groups of the self-employed who were more likely to be saving in a pension in 1998 – in particular, those who had been in self-employed for longer and those with higher levels of income:

- Nearly 70% of the self-employed who were earning over £500 per week were saving in a pension in 1998-99, compared to 24% by 2018-19.

- Over 60% of those who had been self-employed for more than seven years were saving in a pension until 1998-99; by 2018-19 this was 23%.

Heidi Karjalainen, a Research Economist at IFS and one of the authors of the report, said: “Private pension saving has fallen dramatically among the self-employed over the last two decades. This fall is not driven by the changing make-up of the self-employed workforce. Particularly concerning are the huge declines in participation among the more long-term and more well off self-employed: these are groups who will particularly need to save privately for retirement on top of the state pension to avoid falls in their standard of living when they stop work.”

According to Karjalainen, given that other financial assets do not seem to be acting as a substitute for pension saving, policymakers are “right to be concerned” about these trends and to be considering how to make it easier – and to encourage – the self-employed to save more.

In 2018–19, the Department for Work and Pensions estimated that only 14% of the self-employed participated in a workplace pension, down from 35% in 2003–04. In contrast, in 2018–19, workplace pension coverage among employees stood at 73%. Even among employees not eligible for automatic enrolment, workplace pension membership stood at 32% (i.e. more than twice the rate seen among the self-employed).

Furthermore, the IFS said that the report indicated that historically, employees have often been able to accrue greater state pensions than the self-employed, although since the introduction of the single-tier state pension in 2016, this is no longer the case.

“This report analyses state pension provision for the self-employed in the context of these two underlying trends: the rising number of the self-employed and the increasing universality of the UK state pension system. We document trends over time in both the proportion of individuals who, although in paid work, do not accrue a qualifying year towards their state pension and in the value of a qualifying year for working-age adults over time,” said IFS.

Self-care

When people write of self-employed ‘self-care’, saving for retirement must be factored into the equation. If you do not save for your care who will?

There will always be an excuse not to save, something that needs fixing on the house, another treat for the kids, and in these tough economic conditions, we are not taking one’s ability to save lightly. But if you have not set up a Self-Invested Personal Pension, or SIPP, it will be worth looking into one – because you’re worth it. If you are saving for your retirement in other ways, then please share your story with us by getting in touch at editor@freelanceinformer.com.

Points to ponder

- The changing make-up of the self-employed workforce does not explain the decline in pension participation. Over the past two decades the self-employed workforce has become slightly older, less male dominated, and less dominated by full-time workers. The financial crisis dramatically reduced average earnings, which are still in 2018-19 lagging behind their 1997-98 levels. However, it is falls in pension participation after taking into account the role of changes in the prevalence of these characteristics that has driven the overall decline in pension saving.

- Attitudes towards pensions among the self-employed do not appear to have changed over the past decade in a way that could explain the decline in pension saving. Most self-employed believe that saving in property is safer and gives a higher return than pension saving, but this has consistently been the case throughout the period.

- A declining proportion of the self-employed expect to get any private pension income in retirement, suggesting that they are aware that the lack of saving means they will not have access to private pension income in retirement.

- It does not appear that other financial assets are acting as a substitute for pension saving among the self-employed. The proportion of individuals saving in either a pension, savings account, ISA or shares has been declining over the last 20 years, and more rapidly for the self-employed than for employees.

- Trends in owner-occupation rates and average housing wealth are similar between employees and the self-employed, suggesting saving in primary housing cannot explain the faster decline in the proportion saving in a pension among the self-employed than among employees.

- The self-employed are in any given year less likely than other workers to accrue entitlement towards the state pension. In 2016 19% of self-employed workers did not accrue entitlement towards the state pension (because their earnings were too low and they were not in receipt of certain qualifying benefits), compared with 14% of owner-managers and 5% of employees.

- The new state pension is generally much more generous to the self-employed than the state pension it replaced. The full possible amount of the new state pension is much greater than that available just under the old basic state pension. While 35 years (rather than 30 years) of National Insurance Contributions are now required to get the full amount with a full working life potentially extending to 50 years this will be achievable by most.