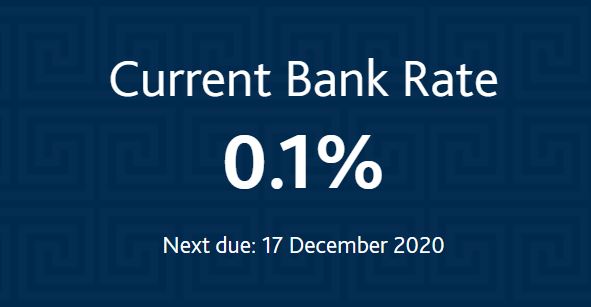

The Bank of England is pumping an extra £150bn of government bonds into the economy as it warned the resurgence of Covid-19 would lead to a slower recovery. The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee has reported that it has left interest rates unchanged at 0.1%, the lowest level in the Bank’s 326-year history.

The new measures take the total amount injected into the Quantitative Easing (QE) programme to £875bn.

It comes before the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, is expected to deliver a statement to the House of Commons later on Thursday to give an update on the government’s plan for safeguarding jobs and growth through a difficult winter.

What does QE mean for you?

The Bank of England wants to encourage spending within the economy, so keeps interest rates low so people can afford to make more purchases and even buy loans.

So, how does the BOE afford to do this and can you benefit in some way, given bank savings interest rates are pitiful?

In times of QE, The Bank issues government bonds, whereby it is lending money to the government. In return, the government promises to pay back a certain sum of money in the future, as well as interest in the meantime.

Buying billions of pounds’ worth of bonds can push the price up and when demand increases so too does the price.

If you are interested in buying bonds or gilts as they are also referred, a good place to start is the UK Debt Management office site here.

What is the MPC saying about the economy?

The MPC sets monetary policy to meet the 2% inflation target, and in a way that helps to sustain growth and employment.

In that context, its challenge at present is to respond to the economic and financial impact of the Covid pandemic. At its meeting ending on 4 November 2020, the MPC voted unanimously to maintain Bank Rate at 0.1%. The Committee voted unanimously for the Bank of England to also maintain the stock of sterling non-financial investment-grade corporate bond purchases, financed by the issuance of central bank reserves, at £20 billion.

“There are signs that consumer spending has softened across a range of high-frequency indicators, while investment intentions have remained weak,” said the BOE.

The Committee’s latest projections for activity and inflation assume that developments related to Covid will weigh on near-term spending to a greater extent than projected in the August Report, leading to a decline in GDP in 2020 Q4.

Household spending and unemployment

Household spending and GDP are expected to pick up in 2021 Q1, as restrictions loosen. However, the level of activity in the first quarter is expected to remain materially lower than in 2019 Q4.

UK trade and GDP are also likely to be affected during an initial period of adjustment, over the first half of next year, as the United Kingdom leaves the Single Market and Customs Union on 1 January and is assumed to move immediately to a free trade agreement with the European Union.

“The fall in activity over 2020 has reflected a decline in both demand and supply,” said the BOE. “Overall, there is judged to be a material amount of spare capacity in the economy. The LFS unemployment rate rose to 4.5% in the three months to August, but it is likely that labour market slack has increased by more than implied by this measure.”