Many workers in the UK are turning to solo self-employment after falling out of traditional employment, a new study finds.

Funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and in conjunction with the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the study found that solo self-employment often serves as a means to recover some, but not all, of lost earnings following redundancy.

As the COVID-19 crisis endures, labour market volatility will create uncertainty over future employment opportunities in certain sectors and occupations, according to Xiaowei Xu, a Senior Research Economist at IFS and an author of the paper. The Researcher expects the economy to see a further rise in solo self-employment as a direct result of onset redundancy and unemployment.

“Solo self-employment is often a fall-back option for workers hit by employment shocks – an intermediate state between employment and unemployment,” says Xu.

Xu believes the anticipated rise in unemployment and subsequent rise in solo self-employment should trigger more care and consideration among the UK workforce. “If so, that would be a group worthy of concern and policy attention alongside the potentially large number of unemployed people,” says Xu.

Best option for flexibility and control

One in nine workers today is solo self-employed – a sole trader with no employees – up from one in eleven in 2008. Solo self-employment accounts for over a quarter of the total increase in employment between the Great Recession and the onset of COVID-19.

Self-employment can be the best option for many workers, giving them a degree of flexibility and control over their work, especially if they have young children or other family members to care for. In recent years, self-employment has been driven by choice.

However, the pandemic and lockdown have urged people to create new business ventures, some out of opportunity others by necessity, The Freelance Informer has previously reported.

“Many workers now seem to be swept into this situation through a lack of good jobs, with this resulting in higher rates of poverty amongst the solo self-employed,” says Peter Matejic, Head of Evidence at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

The researcher says given the extra volatility which COVID-19 brings to the economy, the effects of this trend need to be monitored closely alongside unemployment and low pay.

“Self-employment does have an important role in the economy,” says Matejic, “but it has to be part of delivering good jobs to all parts of the country when it comes to truly levelling up.”

Andy Chamberlain, Director of Policy at IPSE (the Association of Independent Professionals and the Self-Employed), says in recent years the rise of self-employment has been the great success story of the UK labour market, bolstering workforce numbers and driving the economy. However, he is concerned about recent ONS data that is indicating this trend has dramatically reversed.

The ONS statistics for July 2020 revealed that the number of self-employed people in the UK dropped by 178,000 from last quarter and by 105,000 compared to the same time last year (IPSE).

“The ONS statistics show an alarming and avoidable slump in the number of self-employed people in the UK,” says Chamberlian.

“While the Job Retention Scheme has held the number of employee job losses down, the cracks in the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme have hit freelancer numbers hard. Without support, freelancers working through limited companies, the newly self-employed, and other forgotten groups have left the flexible labour market in droves,” he says.

In the last financial crisis and extended downturn, freelancers were integral in building the digital economy and keeping employment figures up. Chamberlian echoes this: “In past recessions, the flexible expertise of freelancers has been crucial for recovery. In kickstarting the economy, the government must, therefore, adopt measures that support and boost the freelancing community. It must also prepare to roll out a fuller self-employed support scheme in the event of a second lockdown – for the sake of freelancers themselves and the wider economy.”

‘Bogus’ self-employment?

Media reports often portray the rise in solo self-employment as resulting from a lack of good-quality alternatives in standard employment and a deterioration in workers’ bargaining power, rather than an indication of entrepreneurial drive or preferences for self-employment.

The gig economy has elevated many people into flexible working, but at what cost? For example, the report cites the high-profile litigation by Uber and Deliveroo drivers, which has focused attention on ‘bogus’ self-employment, particularly in the gig economy, where companies are seen to use self-employment to bypass labour protection laws and shift risk onto workers, said the report.

Earning potential

The study found that after three years after starting their own businesses, those who entered solo self-employment after a spell of non-employment report earning nearly £500 (30%) less a month on average than they did before falling out of employment. This, however, could be misleading if the gig economy is the leading sample.

Notably, with redundancies expected to continue into 2020 and a greater acceptance of remote working, more and more professionals in the IT, legal, editorial, PR & Marketing, and engineering sectors are opting to set up their own consultancies and charge healthy rates. The acceptance of remote-working has also inspired many professionals to set up on their own or work part-time with existing employers so that they can build their freelance business at the same time. This option is not impossible, but it can be a headache for tax purposes, so it is advisable to retain advice from a reputable accountant on how to best set up your freelance business.

But like all things freelance, nothing is guaranteed, which is part and parcel of running any business. There are short-term contracts, there are one-off jobs. And then there is the silence of uncertainty as many self-employed dealt with at the onset of the UK lockdown when clients stopped engaging or buying.

While the self-employed may forego the benefits of an employer-paid holiday, private health insurance, and pension contributions, they can charge rates commensurate with their skills and experience. However, some industries are still paying freelancers below-average pay rates. This is especially true in the fashion and influencer industry, as previously reported by The Freelance Informer.

Job satisfaction

Despite perhaps generating lower monthly income, the sample group of the IFS study reported that becoming solo self-employed was also associated with big increases in job satisfaction and other measures of well-being, even among those that may have been ‘pushed’ into self-employment by a lack of employment opportunities.

“Our research suggests that becoming solo self-employed often increases well-being, despite leading to lower earnings…We should try to understand the desirable qualities in solo self-employment – freedom, autonomy, and authority, for example – and look for ways to foster them in traditional employment relationships,” Xu says.

The study sample consisted of workers aged 25–59. Other key findings include:

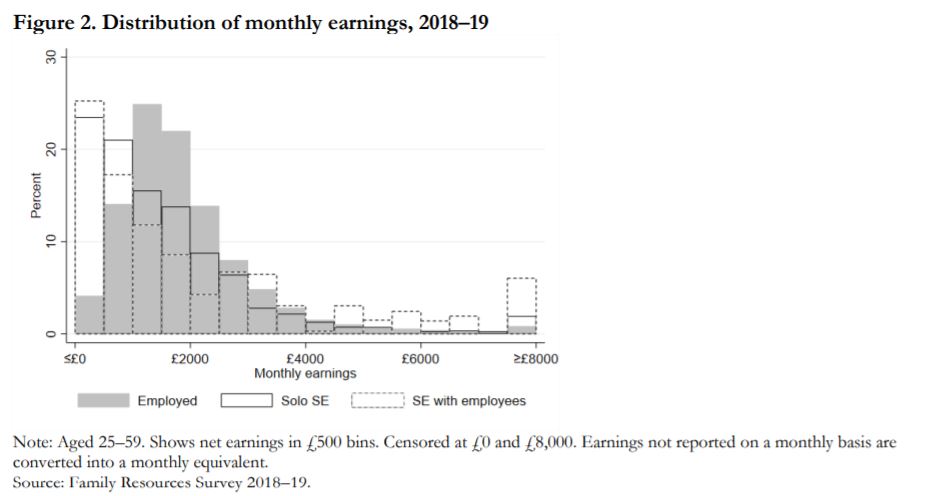

- Median monthly earnings are lower among the solo self-employed than among employees: £1,179 compared with £1,651 in 2018–19. The gap has widened over time, from 21% lower in 2002–03 to 29% lower in 2018–19.

- More than one in four (27% of) solo self-employed workers were in relative income poverty in 2018–19, after deducting housing costs, compared with one in ten (10% of) employees. The solo self-employed were also more likely to report being materially deprived, though the difference is much smaller.

- More than 40% of those moving into solo self-employment were unemployed or inactive in the year before starting self-employment. Many reported having been dismissed or made redundant from a previous job.

- Solo self-employment is often a transitory state. 26% leave solo self-employment within one year of entry, and 38% are no longer self-employed three years later. The vast majority (73%) of those who leave solo self-employment move on to traditional employment.

- Well-being improves markedly upon entering solo self-employment. In particular, job satisfaction rises by 1 point on a 7-point scale, relative to an average score of 4.7 the year before. The improvement in well-being holds on average even among those who fell out of employment in the run-up to entry and among those who did not expect to start their own businesses the year before, who are more likely to have been ‘pushed’ into self-employment.