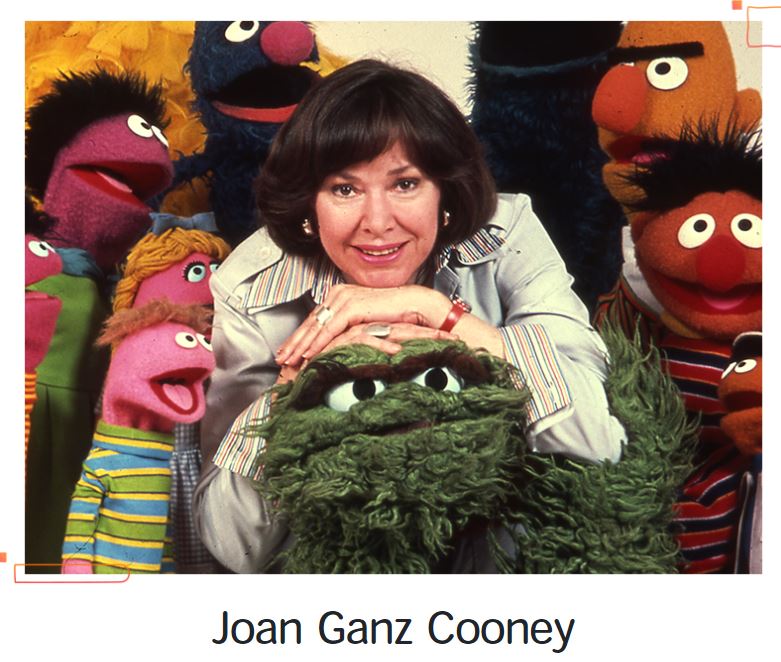

In 1969, one of the most successful and longest-running TV shows in history was born – “Sesame Street.” In its first season, the children’s educational entertainment show won three Emmys, a Peabody, and was featured on the cover of Time magazine. The creator, Joan Ganz Cooney, had a fundamental goal following a sponsored research trip across the US and it wasn’t to make money – despite the wealth of its backers, the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Her vision was to fill the education and cultural gap for North American pre-schoolers from lower-income households. The end result was beyond anyone’s expectations and became an educational media behemoth that to this day is still loved by educators, parents and children across 120 countries.

Can today’s Edtech companies hold a candle to Cooney’s vision and execution while making a profit?

With the uncertainty of a second spike in the global COVID-19 pandemic, Edtech startups, developers, content creators, investors and education ministers need to take a virtual trip back to this magical place called Sesame Street- the world’s first Edtech company. Today’s children are counting on them to create and fund something that is truly inspirational and fills the education attainment gap for good in the UK and across the globe.

Back to Big Bird: the goal of Sesame Street

“It is surprising that perhaps the biggest, yet least costly, early childhood intervention, “Sesame Street”, has largely gone unnoticed,” writes Melissa S. Kearney and Phillip B. Levine, authors of a National Bureau of Economic Research report, EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION BY MOOC: LESSONS FROM SESAME STREET

In 1966, Cooney was a documentary producer at a local televison station, Channel 13, when Lloyd Morrisett, then Vice President at the Carnegie Corporation of New York, offered her an opportunity that would change the landscape of children’s media forever.

The Carnegie Corporation provided funding for a three-month study during which Cooney travelled the country to interview early learning experts and children’s television producers and filmmakers. The report convinced the corporation to partly finance such a project, and Cooney and Morrisett were able to raise the rest of the $8m through the U.S. Office of Education, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the Ford Foundation, according to the Joan Ganz Cooney Center.

Her report, The Potential Uses of Television for Preschool Education, became the blueprint for Sesame Street and Children’s Television Workshop and can be downloaded here.

“This show initially aired in 1969; its fundamental goal was to reduce the educational deficits experienced by disadvantaged youth based on differences in their preschool environment. It was a smash hit immediately upon its introduction, receiving tremendous critical acclaim and huge ratings. It cost pennies on the dollar relative to other early childhood interventions.”

Her report, The Potential Uses of Television for Preschool Education, became the blueprint for Sesame Street and Children’s Television Workshop

Cooney’s original report can be downloaded here.

Well-designed research studies conducted at that time, indicate that the show had a substantial and immediate impact on test scores, comparable in size to those observed in early Head Start evaluations.

Cooney also had a stellar creative team — including Jim Henson, who created the show’s Muppet characters. She also had the foresight to establish a collaborative process with educators and child development researchers to plan the show, according to a PBS report. Great collaboration of talent brought characters such as Big Bird, Oscar the Grouch, Cookie Monster and math whiz Count von Count (along with a cast of human characters like Maria and Mr. Hooper).

According to the same PBS report, “Cooney based Sesame Street’s fast pace, repetition of segments, and multiple formats on 1960s commercial television shows like “Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In,” hoping to bring her educational curriculum to life.”

There has even been an analysis of the effectiveness of Sesame Street and how it can potentially inform discussions regarding the ability of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) to deliver educational improvements, according to the National Burea of Economic Research report. When you think about it, Sesame Street was the first MOOC (Massive Open Online Course). It provided free access to fun learning content to the masses and combined the expertise of cognitive psychologists and educators. That free access bit was also its secret sauce.

What a lot of people may not know is that Big Bird, Kermit the Frog and the gang were nearly homeless in 2015 – the TV favourite’s 50th year in production. The production company behind the business, Sesame Workshop (formerly Children’s Television Workshop), could only make 18 instalments per year on the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) and falling into a $11m loss made matters worse. In essence, “Sesame Street” almost went bust until HBO came along and “saved” it with a multimillion-dollar boost, its financial chief revealed in a Page Six interview. As part of the deal, the number of shows to air each year would jump to 35 with the first show under HBO ownership airing on January 16, 2016

“It was one of the toughest decisions we ever made,” Steve Youngwood, Sesame Workshop’s COO, told The Hollywood Reporter as he admitted that the conversations with PBS were “complicated.”

In 2019, “Sesame Street” could claim a $100m empire, with 5 million subscribers on its YouTube channel — and in June 2018, bosses signed a huge deal with Apple to create new content. There are more than 150 versions of the show being produced in 70 languages, everywhere from South Africa to Bangladesh, with more countries on the way.

Notably, “Sesame Street” puppeteers have made trips to Jordan in recent years to help set up a new Arab-language production aimed at children displaced by the Syrian refugee crisis.

The thing is, most online tools are not free, save for Youtube and other open source sites. Can Edtech companies bring the best of both worlds by having strong revenue models, inclusivity and education attainment at its heart?

Attainment figures not looking good

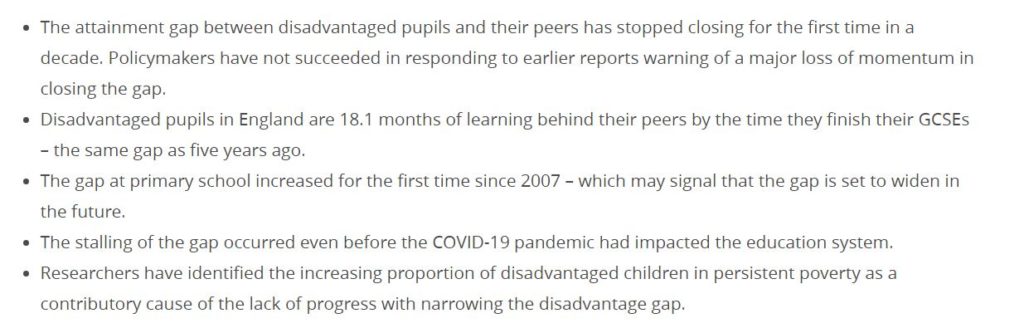

This week The Education Policy Institute (EPI) has published its Annual Report on the state of education in England, including the attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers. Here are some of its findings:

Digital tools are only valuable if attainable

A major challenge for remote learning is rampant inequality in access to technology, says the World Bank. “Digital content can be distributed across multiple delivery channels and in order to reach all children at scale, education systems must prepare multi-faceted responses leveraging all available technologies – print, radio, TV, mobile, online, and print utilizing a combination of these mediums to ensure students are engaged and learning,” says a World Bank report.

The report suggests that for a mixed mode delivery to become the ‘new normal’ to reach all students, the stark inequalities in access to the Internet and devices must be addressed.

Education at its core is a “social endeavour” and teachers must be empowered to use technologies to engage students in learning, according to the World Bank.

However, teachers must also have the funding to share technology with students across several types of media based on a student’s individual access to technology and in a safe and suitable studying environment, which is not always at home.

“A re-imagining of how content is designed should address the unique skills and background of learners in order to provide multiple pathways and opportunities for the students to realize their potential,” says the World Bank report.

Any child should be able to walk into their school or local library and ask to get free access to excellent and entertaining online educational content. And Edtech content and IT infrastructure developers should be inclusive in their mindset when developing products. They have to think of those kids that may not own their own laptop; that speak English as a second language. They must remember that kid that has to share one iPad or mobile phone with another four family members. Where, how and on what device can that kid get free access other than at home? But these IT and content developers are often working for startups on lean budgets, so they have to consider a viable revenue model. In essence, they need as much bang for their buck as possible if they want to reach hundreds of thousands of kids.

Developers and teachers can check out companies such as Zzish, that aim to provide developers with tools to create clever apps and to reach a wider audience. They can also look to Apple, who is tapping into the remote learning market, with campaigns such as the Apple’s Community Education Initiative (CEI) in the US. UK developers and those in other markets should look into these tools and initiatives and approach a similar model for their home market.

“Ten years from now, I want my students to look back and see the powerful impact remote learning had on them, and that it was a positive transition,” says Portrice Warren, an educator taking part in the CEI. “There are going to be a lot of challenges, but I won’t let my students fall through the cracks. I know there is going to be a lot of hard work involved, but in the long run, it will pay off. And that investment in their future is my purpose,” says Warren.

Make do with the tech we have?

Not all schools systems or counties have Apple working with them directly. Until similar initiatives, such as the CEI are available to other markets, sometimes educators and developers have to work with what they have first.

In this regard, The World Bank is calling for personalized, modular, and data-enhanced digital content. “In this coping phase, rather than developing new content, which takes significant time and expertise, countries focus on curating existing (especially free, ‘open’) content and aligning it to the curriculum.”

To prepare for the future, countries should develop short, modular content for distribution over multiple channels, with mobile as a primary channel. Digital content is also the data gathered from learners and the rules or algorithms interpreting that data, says the World Bank report.

So, you want to get into Edtech?

If you are already working in the education sector or have a driving passion to join your existing skills and experience to the sector in a new and dynamic way, then start to do your homework because things are evolving.

In addition to going on job boards, such as Edsurge.com, you may want to familiarise yourself with established Edtech companies that have raised considerable startup capital in recent years, recently raised capital this year and mention ‘growth’ or ‘expansion’ in new markets or product lines. You can easily find this information by reading company press releases, company blogs in addition to news story searches. By doing learning more about the sector you can start to see some trends emerge or even content, revenue model or IT infrastructure gaps where your skills may be attractive to an Edtech startup.

Here are a few Edtechs to look into to start:

- Guild Education (US-based but has remote positions). Check out this interview with the company’s co-founder, Rachel Romer Carlson.

- Kano Computing is an international computer company that also provides education and training to the school sector. They are hiring in the US and UK.

- Memrise is a language learning site and app that caters to students, business people and anyone who wants to learn another language fast. It looks like an amazing place to work, too. Check out this video.

- Cognassist, a Newcastle-based company with operations across the UK that provides online assessment to quickly and easily identifying learners with additional learning needs, assessing those needs and providing a robust report evidencing those needs for the education and corporate sector. While they prefer to hire for permanent positions, they also hire contractors and freelancers.

Look out for our upcoming interviews with recruitment firms hiring in Edtech to find out which roles and skills are in highest demand.